Hi! It’s Zoe. This essay came out of a writing bootcamp I just completed, which has prompted me to think about why I write. I learned a few important things: 1) You have to tell the stories of your past to become the next version of yourself, and 2) it’s OK to make art and write and create not because you want to go viral, not because you think a piece will change lives, but just because you need to.

This essay is about an experience that shaped who I am.

Major shoutout to who was a great editor and pushed me to find the truth at the bottom of this story.

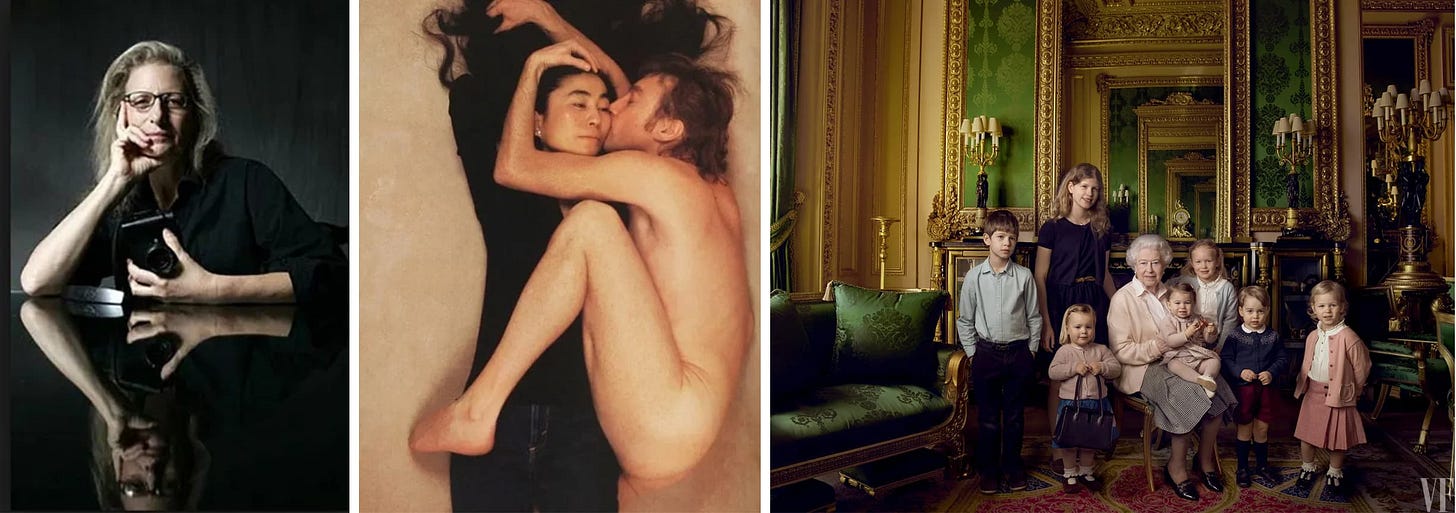

One of the most famous portrait photographers in the world, Annie Leibovitz, has her studio in a quaint three-story, red-brick townhouse in Greenwich Village on the corner of a quiet block lined with trees.

As an intern there, I spent most of my time in the basement.

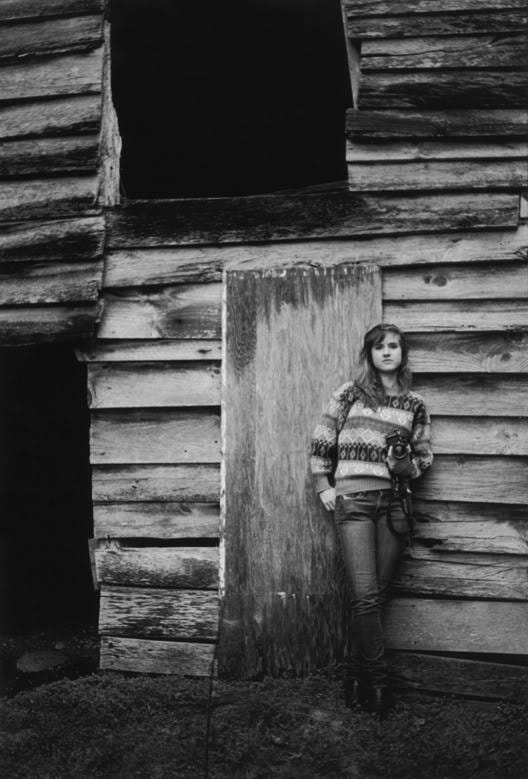

I was seventeen that summer. As part of the interview, I submitted a portfolio of my photographs. One of the images, a portrait of my two friends, had been recognized by the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, a prestigious program for students in grades 7-12.

The original photo hangs in my mom’s dining room, adjacent to one of my paintings, in a house where every single wall is hung with a piece from three generations of family art.

Growing up, I didn’t have a lemonade stand—I sold drawings for 50c to tourists out of my mom’s rented studio in an old torpedo factory. We weren’t allowed to watch TV on weeknights, so I made dioramas and collages instead. Mom eventually moved her studio to the attic; she painted for a living. My dad worked for a decade at the National Gallery of Art. Both my maternal grandparents were painters, and my aunt had a business in textiles.

My family doesn’t go to church. We worship art.

In the basement of Ms. Leibovitz’s studio, I happily rifled through thousands of 11x14 photocopies of old magazines and art books: her reference library. There were images from vintage editions of W Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, LIFE; Xeroxes of books from Henri Cartier-Bresson and Man Ray; unlabeled images of nameless models in flamboyant clothes and poses.

Between coffin-sized Pelican storage trunks and coil upon coil of orange extension cord, I thinned and organized the collection, which was haphazardly grouped in plastic tubs stacked to the ceiling. The discarded pages lapped at my feet, an ocean of art and history.

Once in a while, the studio manager sent me to fetch a coffee or lunch from a nearby cafe. I brought Ms. Leibovitz oatmeal once (with raisins). She was sitting at an enormous wooden table, alone, signature glasses, thin graying hair, waiting for a meeting to begin.

Annie Leibovitz is a woman who has stood within inches of the most celebrated artists, musicians, actors, and public figures of the last four decades: John Lennon, The Rolling Stones, Meryl Streep, Michael Jackson, Queen Elizabeth, Leonardo diCaprio, Angelina Jolie. I slid her paper cup of oatmeal across the table. She smiled at me and said “thank you” when she took the white plastic spoon.

I didn’t say a thing. I retreated to the basement.

One afternoon, after a long morning spent between the Pelican cases, the studio manager called me in for an errand. I expected to run to the bodega for seltzers, or maybe the printer in midtown. I did not expect to be sent to fetch an original Keith Haring that day.

Ms. Leibovitz had photographed the young street artist four years before his death; in the photo, a version of his famous “Radiant Baby” is painted behind his head. Haring gifted Leibovitz the canvas from the set after the shoot, and she planned to hang it in her daughter’s room. Someone had to retrieve it from the archive.

The storage warehouse was dim and cool. I walked silently behind the employee who led me past shelf after shelf of sealed storage and kept my head low, sneaking glances. There was absolutely nothing to look at, but who knew what kind of priceless art was in those bins? My Keds padded quietly on the slick floor. He retrieved the cardboard-wrapped parcel from a wall of shelving and walked with me out to the street, tucking it into the trunk of a yellow cab.

I sat quietly in the backseat as the driver sped downtown, the West Village blurred out my window. One of pop culture’s most celebrated images was twelve inches from my tush.

Back at the studio, the office manager set the painting on the island in the basement, and a small group gathered as if to pray. Off came the packing tape, the extra layers of cardboard. The room was hushed. The painting was laid bare.

Before that day, I’d seen some version of Radiant Baby a dozen times before in pictures and on t-shirts, but the physicality of a canvas is so different from the slick pages of a coffee table book. The painting in front of me was real. One afternoon, years ago in some art studio, a young Keith Haring stood inches from that same canvas and held a can that sprayed that same paint. It was like I was standing six inches from Haring himself.

Something inside me shifted.

In that moment, standing inches from that canvas in the studio of a world-famous photographer, I arrived. I was “in.”

The art world I’d only seen in books—the one where artists not only succeeded but became legendary—was literally at my fingertips. And I thought… maybe I could belong.

The group spent a few moments in silent prayer, reverent over the canvas. Then I packed my things to head for the subway. It was a long ride back to my aunt’s apartment where I was living with my mom that summer in Carnegie Hill.

“Mom!” I yelled, unlocking the heavy apartment door, which swung open onto a dark and quiet hallway. The walls of the narrow space were lined with art.

Mom was making coffee in the white linoleum kitchen.

I dropped my messenger bag on a chair next to the tiny counter. “Guess what I got to do today?” I asked. I recounted the cab ride, the package, the painting. She did not need me to explain who Haring was.

From then on, I knew. Art wouldn’t just exist for me in coffee table books, or on my family’s walls.

It wasn’t just a legacy—I would make it my life.

Beautiful rhythm between the grand and the minute, between styrofoam cups and big dreams. Good story, good storytelling.

So you’ve stood next to Annie Liebowitz and a Keith Haring and I’ve stood next to you. I’m feeling kind of special today! Great story and I love the combination of storytelling with words and photos.